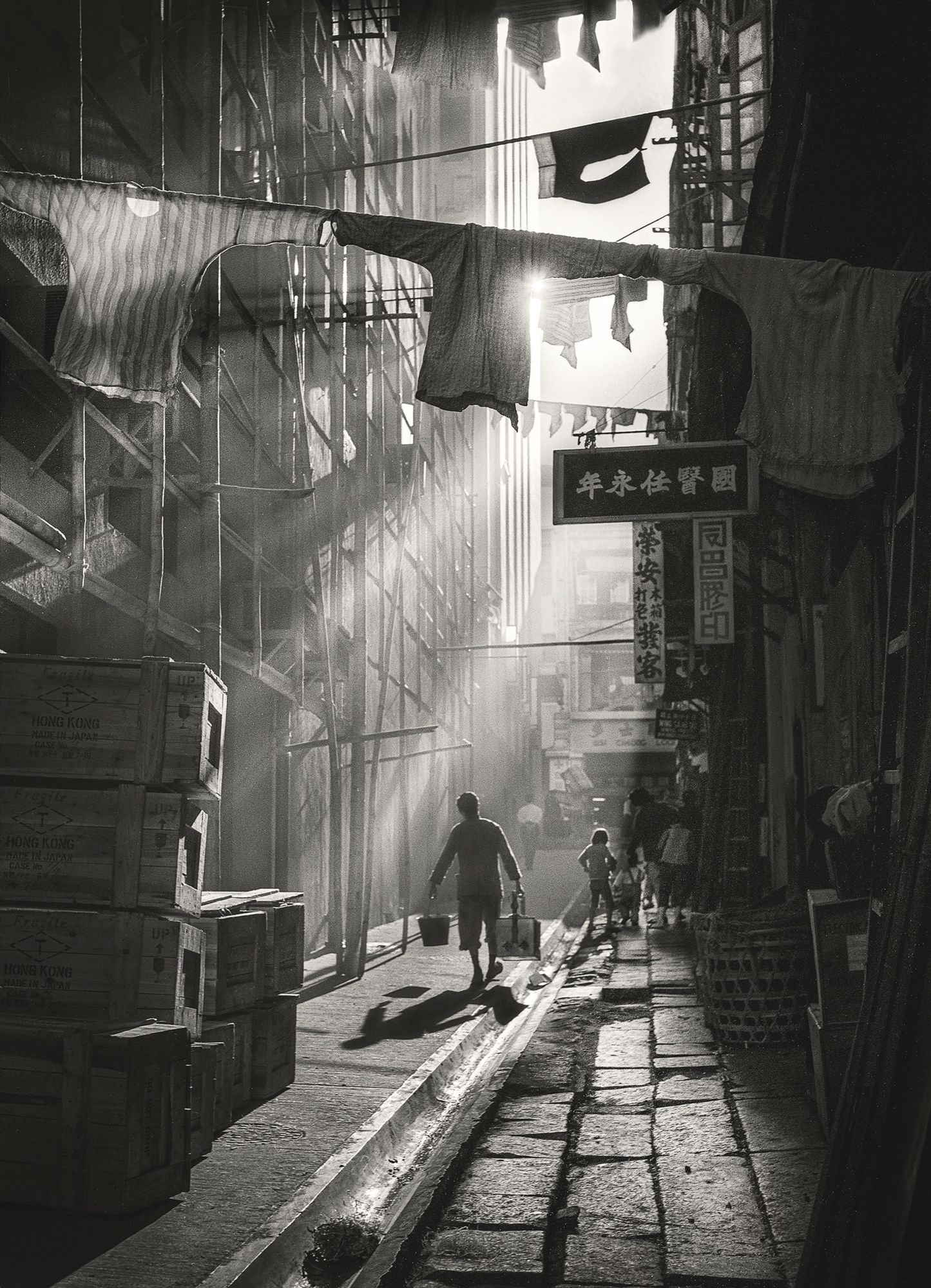

The son of legendary Hong Kong photographer James Chung Man-lurk reprints his father’s rare photos to give a glimpse into the city’s past

The photograph is faded but the expression on the young man’s face is clear. He stands in the Macau sunshine, hand in pocket, smiling with pride and a camera around his neck: a 3.5F Rolleicord, a highly sought-after instrument in 1962, when this picture was taken.

James Chung Man-lurk, here making a concerted effort to pose like his namesake, Hollywood star James Dean, would himself go on to find fame as one of Hong Kong’s most respected photographers. He died in 2018, but his work is being kept in the public eye with two forthcoming exhibitions: one beginning this autumn at gallery F22 Foto Space and the other next January in F11 Foto Museum, featuring prints reproduced by his son Stanley Chung Charn-kong.

A career in photography was far beyond Chung’s imagination as a child born in 1925 in a small farming village in Guangdong province. He dropped out of secondary school to work as a farmer and carpenter while living with his grandmother. In 1947, amid the backdrop of the Chinese Civil War, Chung, then 22, joined swathes of other mainland Chinese who took boats across the Pearl River Estuary in search of better job opportunities in Hong Kong.

See also: Explore Gender Beyond The Binary Through The Lens Of Chinese Photographer, Luo Yang

Captured Interest

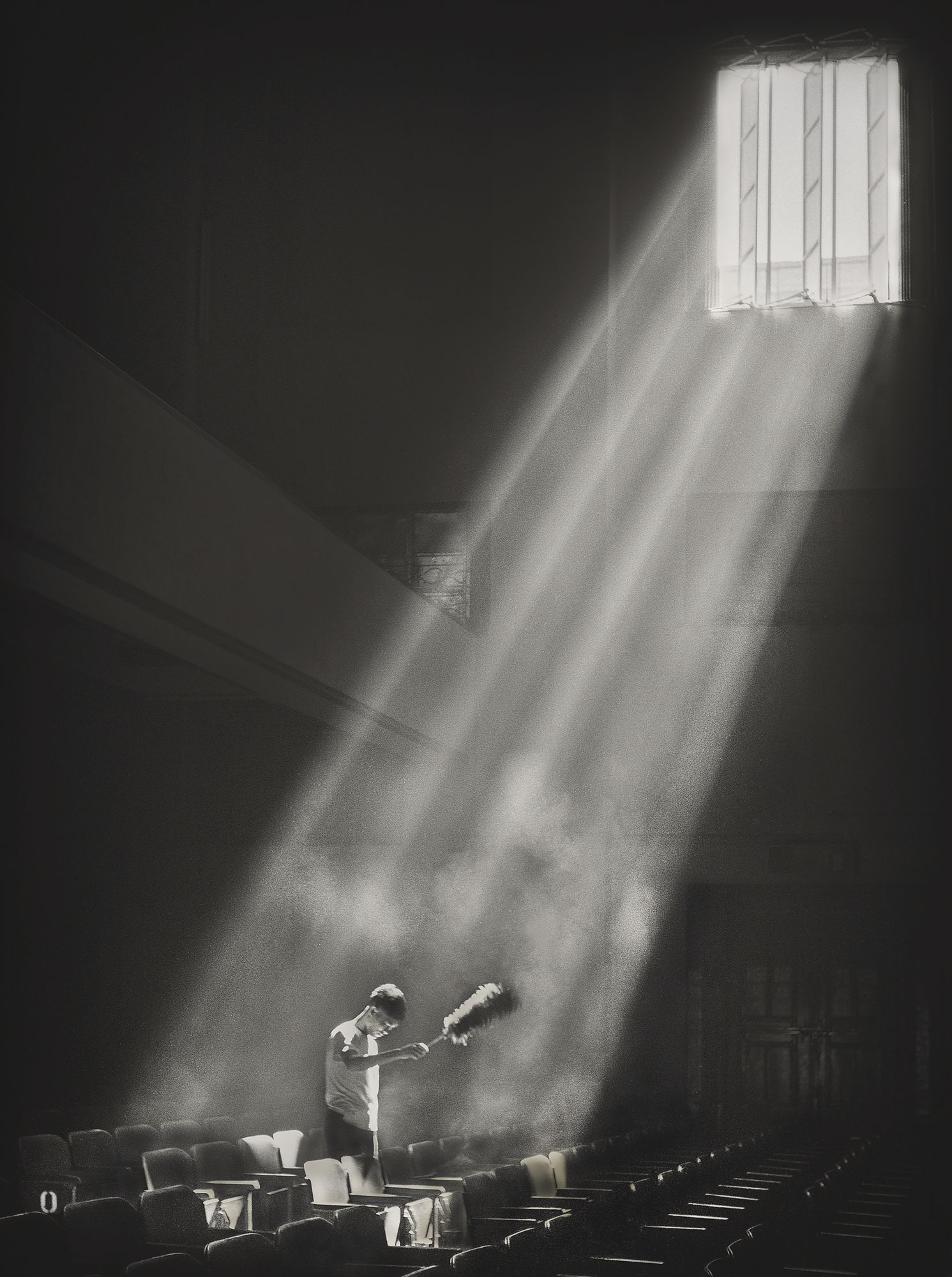

He arrived here hoping to find an apprenticeship in any industry that would allow him to make a living, and ended up using his savings to learn art from Chan Hak-shun, the senior apprentice of Xu Beihong, the Chinese ink painter famed for his paintings of horses that combined Chinese brush techniques with western composition. He also started an apprenticeship in the visual arts department of Wan Chai’s Oriental Cinema at a time when movie posters and other advertisements were illustrated by hand.

Those portraits sparked Chung’s interest in photography. At that time, the German-made 3.5F Rolleicord and the newer Rolleicord Vb F3.5 models were favoured among amateur photographers as they produced photos with excellent depth of field and detail. “He had been drooling over the cameras for quite some time,” says his son Stanley, 64. However, with a family to feed, and a monthly salary of about HK$60 (while difficult to compare to today’s dollars, that sum would likely be about HK$10,000), the aspiring photographer could only borrow someone else’s camera and submit photos to newspapers, making just enough money to buy more 125-exposure rolls, which cost HK$1.25 each.

In 1957, after saving for a decade, Chung finally bought his first camera, sharing the cost with a colleague. Despite being self-taught, Chung was published by several magazines and newspapers, including the state-owned Ta Kung Pao, the oldest Chinese-language newspaper.