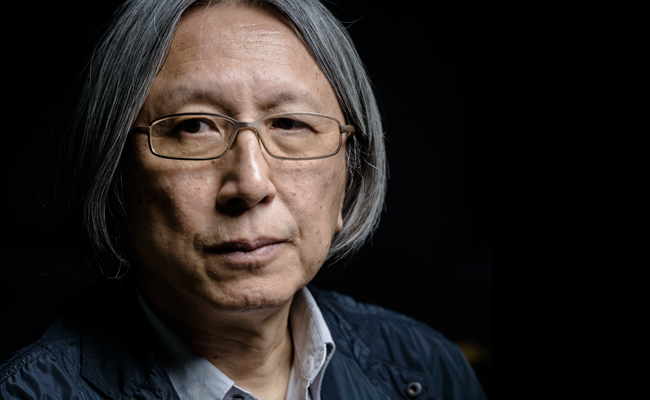

We sat down with the acclaimed Chinese author to talk about his latest novel and the controversies of his craft

Shanghai-born and now Beijing resident Koonchung has been under the public eye ever since the release of his controversial science fiction novel The Fat Years. Set in 2013, the book features transcultural characters – much like Koonchung himself, who has lived or worked in the States, Beijing, Hong Kong and Taiwan – who realise that an entire month has gone missing from official records, and are determined to figure out how and why. The novel was released in 2009 and was Koonchung’s first foray into fiction, after a long stint in journalism in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The appointed Author of the Year at the Book Fair (July 17-23) will return to Hong Kong to introduce his latest novel The Unbearable Dream World of Champa the Driver. Similarly and also contrariwise to his debut, Koonchung’s second book chronicles the life of a young man living in Asia and explores the delicate relationship between Tibet and China. The title character Champa is a Tibetan chauffeur living in Lhasa who embarks on relationships with his Han Chinese employee and her daughter.

Koonchung talks to us about fiction writing, the controversies of publishing in his homeland, and Tibet.

HongKongTatler.com: The title of your second novel is The Unbearable Dream World of Champa the Driver. How did the idea for that novel seed itself?

Chan Koonchung: In the early ‘90s, I was working with director Wayne Wang as a producer on a few of his films and ended up in Hollywood working on a Francis Ford Coppola film. We started researching the idea for a film about the 15th Dalai Lama and from there I became interested in the history and culture of Tibet – prior to that I had no knowledge whatsoever about the place. I have been thinking about writing a novel exploring the Tibetan China relationship ever since.

HKT.com: There is a very interesting triangulated relationship between the main protagonist, Champa, his employee and his employee’s daughter.

CK: I just thought it would be more intriguing to represent Tibetan and China relationships as a sexual relationship – there are certainly more dimensions. Manipulation, dependency, longing…a lot of emotions. Han Chinese and Tibetan are not blood brothers. Champa’s relationship with the older lady’s is a more political one, there’s a clear power dynamic, whereas with the daughter he feels more equal, yet there are still major cultural differences.

HKT.com: What is the character of Champa like in comparison to other youngsters living in Beijing?

CK: He’s like any young person in the world; he wants a good life. Champa wears designer jeans, loves to drive, and of course, he likes sex. He’s in self-belief that he’s not any different to any young person in Beijing, but actually he’s incredibly cosmopolitan because of his background – he’s Tibetan, grew up in Lhasa, and his family works for the government. He can’t get a passport but is still kind and friendly to the Han Chinese.

HKT.com: Your first novel, The Fat Years, was never published in China but available online and overseas. Were you afraid of severe repercussions?

CK: I’m never sure what will happen to me. The Fat Years has been available online for a while but recently they’ve started shutting down a lot of virtual bookstores. They never speak to me directly. Of course, I am anxious.

HKT.com: A lot of people have compared it to 1984, but in fact when the novel was published in 2009, you had already set it in the not too distant future of 2013.

CK: The Fat Years is not a dystopian novel. I wanted to write about the present – actually in my mind the novel is set in 2008, because it was an important year and that was when the mentality about China had already begun shifting. The novel is about the new normal existing in China, the wealth and the superpower, which I think will go on for quite some time, at least another ten years.

HKT.com: Do you find that your journalism background has helped or hindered you in writing creative fiction?

CK: I am definitely influenced by my brief journalism career. But actually, that kind of journalistic attention to detail and historical facts is also similar to the style of a realist fiction writer. The 19th century realist writers were are all very particular about that – think of the level of detail in The Red and Black by Stendhal, which is based on a court case. The difference is that fiction allows me to integrate different facts into one text, whereas if I were writing a journalism piece, even long form, you can’t fit that many details into it.

HKT.com: With fiction, do you feel the obligation to give a representative opinion of your country? Especially given the subject matter of your novels?

CK: Fiction allows you to be ambiguous in a good way. As long as I’m truthful, I feel I don’t really need to provide any solutions or answers. With Champa, I feel likethere are expectations when it comes to writing about Tibet – you’re either expected to have a very romantic vision or a very political reading of the place. Champa is neither. Fortunately I am over 60 now so I also don’t feel the need to please many people!

The Chinese version of The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa the Driver is available in bookstores across Hong Kong. The English version will be published in early 2014.