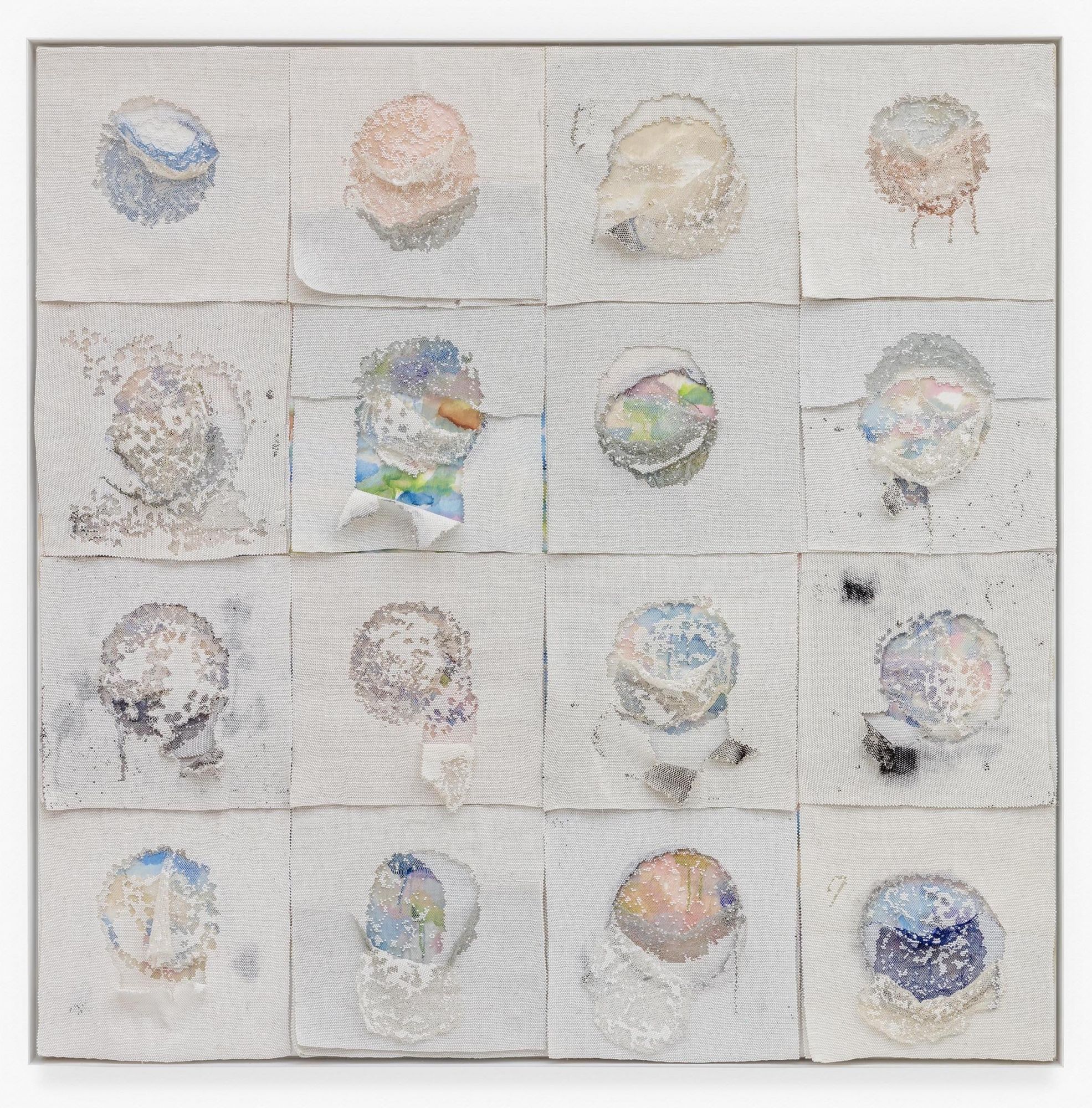

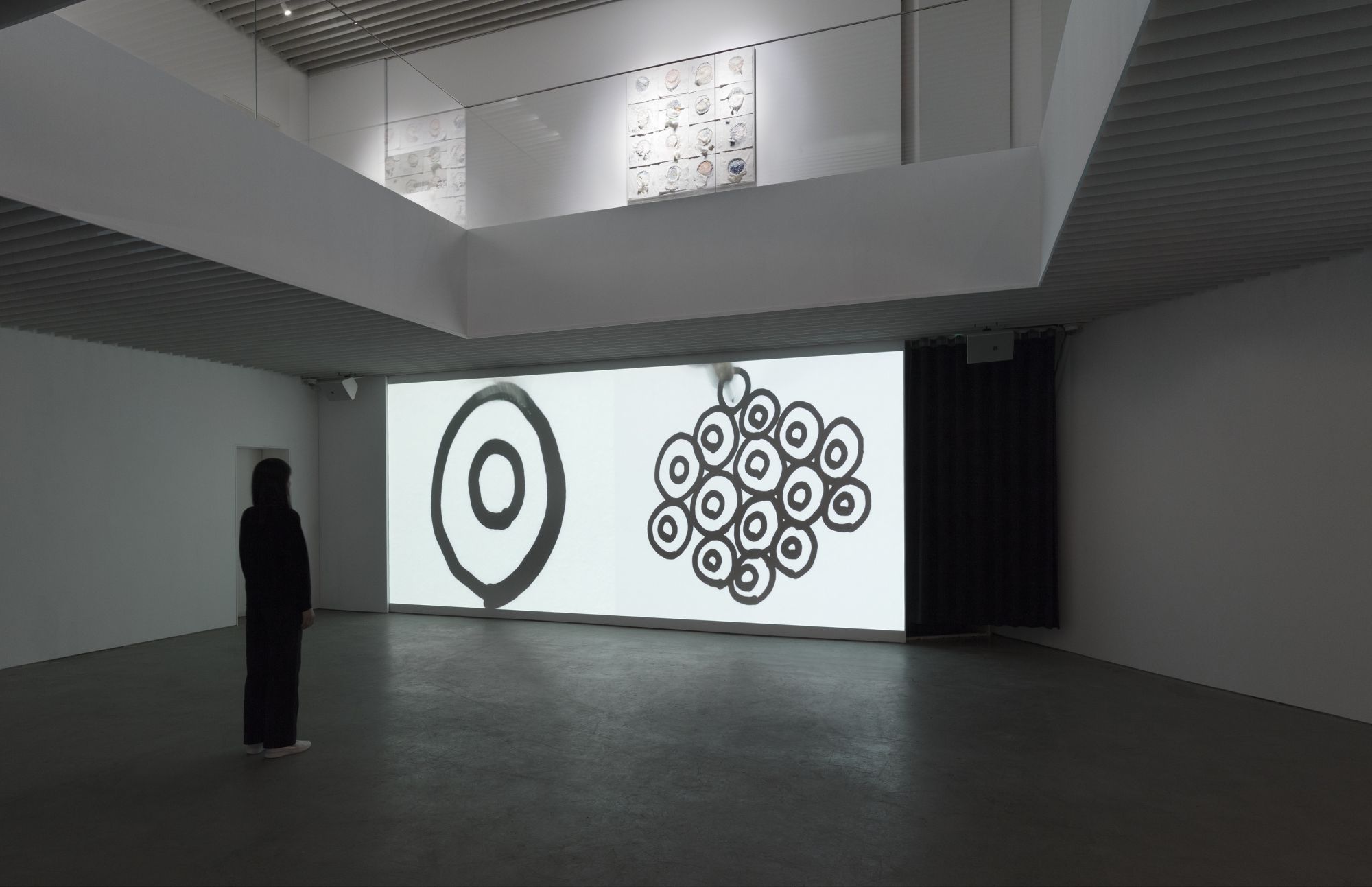

Liza Lou has carved out a career working solely with glass beads. As Lou's new series goes on show in Seoul and Lehmann Maupin prepares to exhibit a work at West Bund Art & Design fair in Shanghai, she explains how her focus is shifting from the body to the mind

Liza Lou worked for more than a decade in a studio in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, that buzzed with activity. The American artist and her team of artisans sat elbow-to-elbow every day weaving thousands of glass beads into the shimmering paintings, tapestries, sculptures and installations that Lou has been making for more than 25 years. While they worked, they’d talk. They’d hum. They’d eat. They’d laugh. Occasionally, they’d break into gospel songs, their rapture reverberating around the room as they wove bead after bead, thread after thread, day after day.

So when Lou moved alone to work in a studio in Los Angeles four years ago, she was struck by the silence.

“Moving home was really difficult at first,” she says. “The studio in South Africa is special. It’s a shared endeavour and we all have this mutual love for this process, and love for each other. All of us have our own families, but then there’s the family life in the studio. You spend hours and hours and hours with people chatting around a table, sharing your life.

"But I was faced with this decision because at a certain point you’re giving up your citizenship and you have to ask real questions about what you’re doing with the rest of your life. I have a daughter; I have a husband. There was a time when I couldn’t imagine leaving, but sometimes when you’re faced with a big choice you can’t actually think it all through; sometimes you just have to do and then let it take care of itself. The answers are in the doing—that became my epiphany.”

Lou may well have learned that from her labour-intensive art, the meaning of which can be found in the way it’s made. For her first major work, which was completed in 1996, Lou created a life-size replica of a kitchen using millions of glass beads. Tony The Tiger smiles out from a beaded purple cereal box. Strings of blue beads pour from beaded taps, splashing into a bubbling beaded sink filled with beaded plates, bowls and teacups.

Lou sees the gleaming installation as a monument to unsung labour, such as cooking, cleaning and sewing. Like these jobs, the making of Kitchen was monotonous and often took place in snatched moments, when Lou wasn’t working as a waitress or shop assistant. “I thought Kitchen would take me three months and it took five years,” recalls Lou. “The actual doing of it was incredibly difficult, tedious and frustrating. But when I came to realise that the work itself was a metaphor, that it was about process and not completion, then I came to a deep sense of peace.”

Kitchen caught the eye of Marcia Tucker, the late founder of New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, who exhibited the sculpture—and pushed Lou into the public eye. For the next three years, Lou made Backyard, a 528-square-foot installation of a garden featuring 250,000 blades of grass, each a snip of wire strung with green beads.

The threading process was so time-consuming that it would’ve taken Lou more than 40 years to finish the installation alone, so members of the public volunteered to help. Watching them, Lou became fascinated by how everyone produced such different work, even though they were all using the same materials and following the same instructions. Some blades of grass were poker straight, others were crooked; the oil from some people’s hands left the beads shiny and bright, while other beads came back dull.

See also: How Former Domestic Helper Xyza Cruz Bacani Became A World Class Photographer